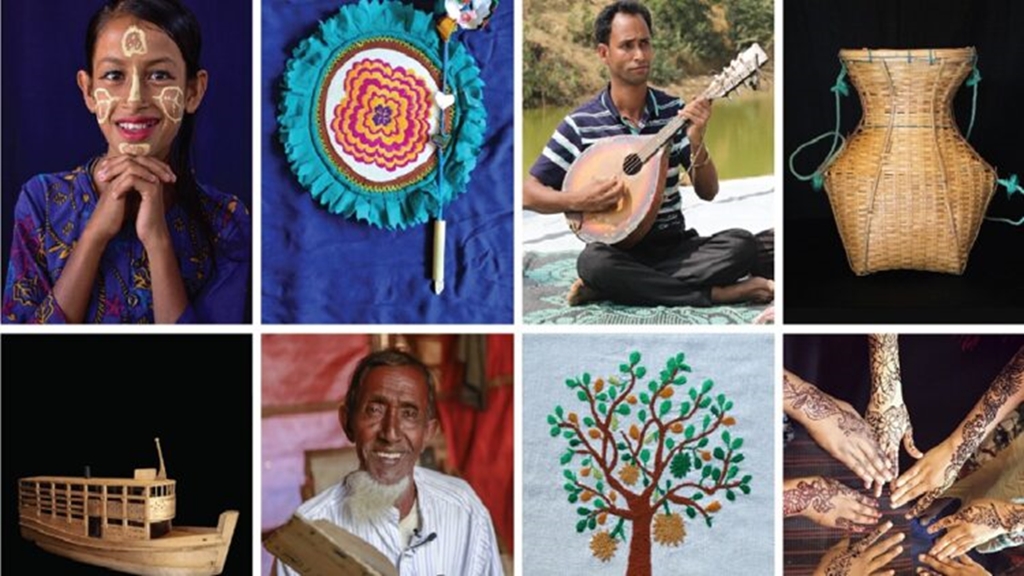

In exile in Bangladesh, a bittersweet revival of Rohingya culture

- 08/05/2019

- 0

By Poppy McPherson, Simon Lewis

KUTUPALONG REFUGEE CAMP, Bangladesh (Reuters) – Chain-smoking singer Gudar Mia, who recently turned 80 in a refugee camp in Bangladesh, lit another cigarette, closed his eyes, and crooned the opening words of a Rohingya folk song.

“Sorry, my throat is not good,” he said, taking a puff as he sat cross-legged in the home of his lifelong friend, Amir Ali, a violinist in his mid-seventies.

As young men, back in Myanmar, they had played together in a wedding band, touring their native Rakhine state on the western border performing on moonlit nights beside the rice fields.

“We were hired every day, sometimes we couldn’t go home for 20 days,” said Amir Ali, a bone-thin man with hollowed cheeks and a faraway look.

Now their venue is a bamboo shelter in a Bangladeshi camp on the edge of a trash-filled swamp, their audience a curious crowd of fellow refugees. But for the first time in decades they are free to play music.

In recent years Myanmar imposed debilitating restrictions on the Rohingya, a Muslim minority demonized as immigrants from Bangladesh. They were prevented from traveling, gathering in groups, and expressing their ethnicity. Getting permission to perform was nearly impossible, refugees said.

“Back in Myanmar, we couldn’t gather more than 10 people, so how could we sing?” said Amir Ali, idly strumming the violin and cradling his baby nephew.

It had been a long time since the band’s last wedding when, in August 2017, soldiers arrived in their quiet village in northern Rakhine State and burned it to the ground. The sweeping crackdown, which the United Nations has said was executed with genocidal intent, drove 730,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh.

Now home to close to a million people, including those who fled previous waves of violence, the camps comprise the world’s largest refugee settlement.

There, Rohingya society is re-forming. While life in the camp is bleak and monotonous, refugees say Bangladesh offers relative freedom compared with the apartheid-like conditions they endured in northern Rakhine.

“PLAY AN OLD SONG!”

On a recent morning, several hundred Rohingya, including the wedding band, crowded into the office of a local community organization for a ‘Rohingya Traditional Affairs Day’.

Someone rigged up a large speaker normally used for the call to prayer to amplify a harmonium, an accordion-like instrument, and an ensemble of musicians including Amir Ali the violinist, now deafeningly loud, struck up with a high-tempo jam.

“This is a traditional affairs event!” one of the organizers cried out, gesturing at the players to stop. “Play an old song,” he said.

Known as hawla, the old songs are slow and normally played at weddings, love stories that revolve around the towns of northern Rakhine, traditions like flying kites, and the rhythms of rice farming.

They involve frustrated love affairs and travel by boat and motorcycle between the villages. Unlike newer songs, they are not about recent suffering, but rather a peaceful time before.

Amir Ali and Gudar Mia grew up in the same village, Hlaing Thi, in Maungdaw township, close to the Bangladeshi border. Amir Ali, from a wealthier family, learned to play violin from an relative who owned one.

He forged an imitation instrument out of bamboo before later buying one in Bangladesh. “The whole day he was playing the violin,” recalled Gudar Mia, who lived across the river and memorized old songs from his relatives as a child.

“Mostly we sang in the farmland while we harvested our crops, and sometimes in the moonlit nights we sang and danced,” he said. “At that time there were no restrictions.”

After 1978, when the administration led by General Ne Win led a crackdown on the Rohingya that drove tens of thousands into Bangladesh, restrictions on the village tightened, with most villagers unable to travel. Gudar Mia never ventured further than a few miles from Hlaing Thi.

“Only rich people could get the permission to hold (wedding) ceremonies,” said Amir Ali. “We could not earn money, like earlier. I was very disappointed.”

‘NOT AN ETHNIC GROUP’

In Myanmar, where ethnicity is linked to citizenship, the authorities and much of the public do not recognize the Rohingya as an ethnic group, and expressions of culture are restricted. In 2015, five men who published a calendar featuring the phrase “Rohingya is an ethnic group” were jailed for causing “fear or alarm to the public”.

At the traditional affairs event, after the music, the crowd gathered for traditional food, including a sweet dish known as modhu baator or “honey rice” usually eaten during the hottest time of the year to cool down and luri feera, rice-flour flatbreads made during festivals to be eaten with beef or goat curry.

“When we talk about (our culture), it becomes fresh in our memories,” said Mohammed Eleyas. “We are an ethnic group with our own strength that we can develop.”

Speaking to Reuters by phone, Min Thein, a senior Myanmar government official at the Ministry of Social Welfare, which is tasked with repatriating the Rohingya, referred to them as “kalar”, a slur reserved for foreigners of South Asian origin.

“Their culture was not restricted, they were able to build a lot of mosques in Rakhine,” he said. “There is a transportation problem for the area not only for kalar but also other ethnics such as Rakhine, Daignet, etc,” he said, referring to Buddhist minorities.

“In Myanmar, Rohingya is not considered as an ethnic (race) according to our history books,” he said, adding that another Muslim ethnicity, Kaman, was the only one recognized.

Rohingya refugees, he said, “can go through the verification process to apply for citizenship when they come back”.

“EACH OF US HAS TRAUMA”

But the Rohingya are facing what is likely to be a long exile. Efforts to start repatriation to Rakhine failed last year, after refugees protested and the United Nations said conditions in Rakhine state were not right for returns.

In the camps, youth leaders see cultural activities as a form of therapy for the young generation, restless, frustrated and with few opportunities for formal education.

Before he fled Rakhine, a young NGO worker named Mayyu Ali secretly mailed verses to local literary magazines under a pseudonym. In Bangladesh, he has hosted poetry training for students and since appealing for submissions for poems to post on a Facebook page called Art Garden has been inundated with more verses than he can publish.

“What I feel is I don’t want to see them with a gun and knife in their hand … I want to see them hold a pen,” he said.

Many of the poems are paeans to northern Rakhine state, others detail the suffering many experienced on their long journey to Bangladesh.

“There are a million Rohingya, each of us has an oral history,” said Mayyu Ali. “Each one of us has trauma. I want a new generation to write for themselves.”

But for the wedding band, the old songs remind them of all they have lost.

“My village was very beautiful,” said Gudar Mia. “There were plenty of plants, farmlands, big lakes also.”

Hlaing Thi, like hundreds of other villages destroyed in the violence, was burned to the ground, satellite imagery of northern Rakhine shows.

“Back in Myanmar, I felt happy when I played violin, as it was my native country,” said Amir Ali, “Here, we are always sad, so I play to reduce my stress.”

The landscape described in the hawla has gone. But, often, just as before, Amir Ali’s neighbors say they can hear the sound of a violin drifting from his shelter.

Reporting by Poppy Elena McPherson and Simon Lewis; Additional reporting by Shoon Naing; Editing by Alex Richardson