Saya Ali Ahmed: A Rohingya Mentor of a Million Hearts

- 19/11/2021

- 0

By Mayyu Ali, The Rohingya Post

“Not a single brick was found intact. The Japanese troops conducted air strikes and destroyed Kerani Bazar Bridge. Many have been killed.”

These verses are the heartbeat of the villagers. They faced the fire of World War Two and suffered Raat _ poverty; children malnourished and elderly people cringed while lying on the bamboo mash wall inside their thatch-roofed and clay-floored houses. There was no hospital in the area. People relied on traditional herbs. It was during the Arakan Campaign 1942-43 in Arakan, today’s Rakhine State, Myanmar, formerly known as Burma. The Arakan Campaign was the counter attack against the British by the Japanese troops that resulted in hundreds of civilian casualties and widespread infrastructure destruction in Arakan. Some Rohingya still carry physical and psychological scars of the war.

In 1961, Saya Ali Ahmed was born to Mohammed Husson and Roshan Jamal in the village of Dún Bai, today’s Aung Seik Pyin, the same village where the Kerani Bridge was destroyed during the Arakan Campaign. The villagers including Ali Ahmed’s parents suffered the worst of the campaign for years. Ali Ahmed had eight siblings, three sisters and five brothers, and he was the fourth son. His father, Mohammed Husson, was a farmer who worked hard cultivating his paddy fields; however, he wanted to educate at least one of his sons throughout all the evolving obstacles in his life.

“When the Burmese Army came to our home to take us for forced labour, I went with them carrying their bags of rations and other things so that my brother Ali could go to school,” said Nur Alom, 57, one of Ali’s brothers who lives in the refugee camps, Cox’s Bazar. “He has been calm and well-mannered from a young age. He became the favourite son of our parents,” Nur recalled.

Mother is busy making dinner in the kitchen. A sister lays out the Cara, a traditional floor mat made of leaves, and a Dostakhána, tablecloth on the mat. The eldest brother fills mugs with water from a metal jug. Dinner consists of bowls of Faijam rice complemented by pieces of fish and a salver of green water spinach or reddish leaves; this is the fundamental meal of a Rohingya family in Arakan. As soon as the dinner is served, all of the family members sit cross-legged around the mat, and they wait until their father or grandfather starts eating first. A Sarag _ Rohingya traditional kerosene lamp is lit in the middle of the dining mat. The flame of Sarag always burns upwards, and it tells us that one should acquire the knowledge to carry us towards higher ideals.

It doesn’t matter if you can’t afford fish, meat or, Durúskúrá _ traditional chicken roast, a shared meal is always the best taste. The atmosphere of love and togetherness during dining is a great pleasure, and that is how Rohingya children like the little Ali Ahmed learn the importance of love, compassion and solidarity from the very beginning of their lives in Arakan. The little Ali would rush through his dinner, so that he could have Sarag all to himself when the rest of the family went to bed. There is no study table or even a separate room at home for him to study in, but nothing matters to someone who is hungry of knowledge. Ali pulls out his pillow to use as a desk for his textbook, slate board, and short slate pencils. He sits cross-legged, his back supported by the bamboo wall. The Sarag is lit, and he looks around once more to check if everyone is asleep so he can gradually start reciting his school lessons. Sometimes he nods off in a heavy slumber, and his mother comes and insists that he goes to bed. When the day breaks, he takes buckets of rice for his father and brothers who work in the paddy field even before the cockcrow. He helps them for hours before coming back home. Sometimes he was late, but he never missed a class.

“He was very hard-working, he studied at night and helped his father and brothers with the farm during the day,” said Mir Ahmed, his childhood friend. “He was very fond of karate and wanted to be an army in Burmese Tatmadaw” Mir recalled.

Education

In 1967, Ali Ahmed was enrolled in kindergarten at Basic Education Primary School in Aung Seik Pyin. In 1974, he finished his primary school at the same school. In 1978, he passed grade eight at Basic Education Secondary School in Kyein Chaung. In 1981, he passed matriculation (the final exam after 10th grade in Myanmar) at Maungdaw High School. Ali Ahmed was the first person in his family who passed matriculation, his father was so proud of him. His father and brothers worked very hard so that they could send him to Sittwe for further study. In 1982, he began his university studies at Sittwe University. There he studied science for two years before moving to Rangoon University for the last two academic years of his degree.

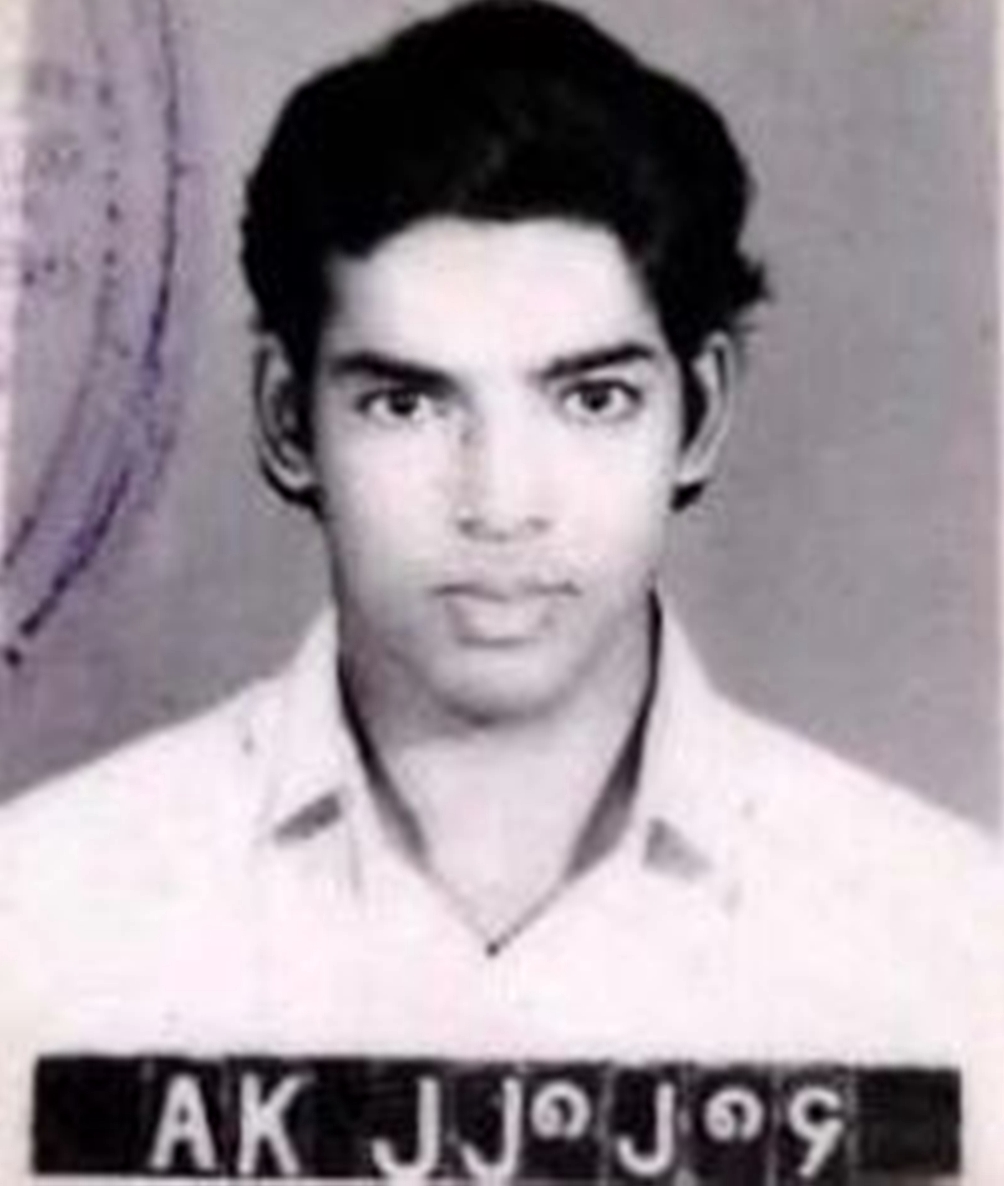

In Rangoon (today’s Yangon), Ali Ahmed met his uncle Mohammed Rashid, a well-known businessman. His uncle financially supported him during this time. In 1985, Ali Ahmed graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Physics from Rangoon University. At that time, Ali Ahmed still wanted to join the Burmese Army to serve the country, but his uncle suggested that he goes back to Arakan so that he could serve the people living in rural areas. Ali believed in this idea and returned home to Maungdaw. A tall, strong, and handsome young man, Ali Ahmed had long and curly black hair neatly combed backward. He dressed elegantly in an ironed shirt and longyi; villagers came to see the graduate, perhaps the first one ever in the village. The Rohingya landlords and senior men in the area came to hear about the news. Zafor Mia, the chairman of Boli Bazar was impressed and sent a proposal to the graduate’s father to wed his daughter to this young man. This was the custom at the time in the Rohingya community. The father was very excited and quickly arranged the marriage. Consequently, in late 1985, Ali Ahmed was married to Laila Khatun.

Tenure

A few weeks after getting married, Ali Ahmed received an offer to teach at Basic Education Secondary School in Taung Phyu where he previously taught Burmese and Mathematics for one year. In 1986 he was appointed as a primary school teacher at the state-run Basic Education Secondary School in Kyein Chaung. At this moment, Ali Ahmed became Master Ali or Saya Ali, and the journey to reign in the hearts of millions of students had begun. Saya Ali was an ardent, passionate, and dedicated teacher. In the same year, he was rapidly promoted to a secondary school teacher and served for few months at Basic Education Secondary School in Tha Man Thar and two more years at Basic Education Secondary School Kyein Chaung. At this point, Saya Ali wanted to become a high school teacher, and he attended the high school classes training for one year under the Myanmar Education Ministry. In 1990, he was promoted as a high school teacher at Kyein Chaung High School. He received 250 kyats (today’s 0.15 USD) salary per month. By now he had four children, and it was very difficult for him to support family with the salary he received, but he never gave up. In 1991, Saya Ali Ahmed went to Yangon for B. Ed (Bachelor in Education). In September, 1994, he outstandingly accomplished M. Ed (Masters in Education) with distinctions in Burmese and Mathematics. He was highly specialised in Mathematics, Physics, and Chemistry and he taught continuously as senior high school teacher at Basic Education High School in Kyein Chaung along with Saya Maung Maung Myint.

“Saya Ali Ahmed and I are like brothers. He and I brought so many changes at Kyein Chaung High School,” said the 68-year-old Saya Maung Maung Myint, the retired Senior Assistant Teacher (SAT). “My prayers and thoughts are with all children and family members he left. I miss him so much” he added.

Saya Ali always looked to the future and wanted to bring about everything in his power. In year 2000, he became the vice chairman of Basic Education High School in Kyein Chaung. In 2009, Kyein Chaung High School became the second matriculation examination board in Maungdaw Township, due to the tireless effort of Saya Ali and other teachers. Saya Ali wanted to be the high school principal but was not able to take this position since he is Rohingya—demonstrating that Myanmar’s discrimination and racism first starts in schools followed by offices and check posts. There are no promotions for Rohingya teachers or civil servants in Myanmar. Since 1962, the government had altogether stopped recruiting Rohingya as school teachers or civil servants in Myanmar.

Refugee Life

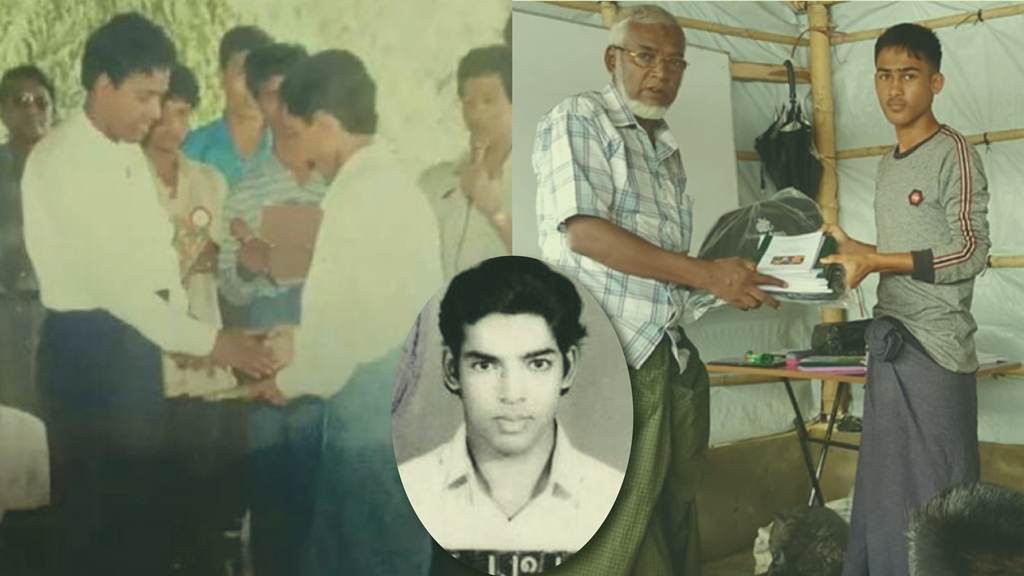

During the violence in August of 2017 in northern Rakhine State, Saya Ali’s home and village were burned to the ground by Burmese security forces, and his family became homeless. On September 2, 2017, he and his family, together with thousands of other Rohingya families, fled to Bangladesh to escape for their lives. Saya Ali lived inside a five-meter-long (16-foot) tarpaulin structure and ate the bowls of brown rice and tasteless lentils in the refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar. However, he never stopped teaching and empowering Rohingya youth. In February, 2018, he and his sons opened a private high school where they teach Burmese school curriculum. In July, 2019, he joined Community Rebuilding Centre (CRC), a camp-based Rohingya high school in Balukhali refugee camp.

CRC High School is located two kilometres away from his makeshift shelter inside the refugee camps. After the Fajr prayer, he would walk to CRC High School in the early morning and arrive for class even before the students. The morning of July 26, 2021, was like any other day. At the class, Saya Ali was as active as ever. No teacher or student noticed any differences in him.

“Saya Ali’s shifts are before mine, and he had already finished teaching his classes in class 10,” said Ro Anamul Hasan, who teaches with Saya Ali together at CRC High School. “After the class, Saya Ali and I exchanged greetings as usual, and I started my class, and he went for his mug of char at a teashop in camp” he recalled.

Saya Ali had his mug of char, and after he went to attend the funeral of one of his fellow villagers who had died in another camp. “Saya Ali and I performed the funeral prayer together. We both were coming back home talking casually” said Nur Kamal, one of his close pupils. “Soon he and I parted ways to each go to our own homes. After just five paces, I suddenly heard a scream of “someone fell down, someone fell down.” I looked and rushed back. I was baffled to see Saya Ali on the ground, there was some blood on his face, yet his school bag was held tightly in his fist.” Saya Ali was quickly carried to a nearby clinic inside the refugee camp where the doctor confirmed that he was dead. It is believed that he died of heart failure since Saya Ali had been suffering from some heart issues for several years. He always believed in giving and sharing, and he served till his last breath. He was only 60.

Thousands of people in the Bangladesh’s refugee camps, Myanmar, and abroad expressed their deep sorrow at Saya Ali’s passing. On social media sites, many Rakhine and Burmese pupils expressed their condolences over the demise of their great mentor. On that day, at five pm, the deceased’s soul was buried at the graveyard nearby Moura Gastala in Balukhali-2 refugee camp, Cox’s Bazar. Thousands of people including many of his pupils paid their last respects to him. Saya Ali left his beloved wife Laila Khatun, his five sons; Mohammed Yunus @ Maung Tin Myint (Masters in English Dip), Mohammed Ideris @ Maung Aye Myint (B. Sc, Math), Mohammed Ismail @ Maung Khin Myint (B. Sc, Physics), Mohammed Esop @ Maung Soe Myint (matriculated), Mohammed Musa @ Maung Hla Myint (matriculated) and the one and only daughter Asiya Bibi @ Ni Ni Myint who passed matriculation in 2008.

Legacy

A white, neatly ironed long-sleeve shirt, a longyi fastened at the waist, a pair of blue and white Sinkyae slippers on his feet, and a small bag hung on the handlebars, he would slowly push the pedals of his old, black Phoenix bike. He would first drive to the Boli Bazar market. A mug of char at Hańsú teashop or Maung Maung teashop is a must for him. Tall with fair, brown skin, he chewed betel and happily greeted everyone he saw along his way. Students—Rohingya, Rakhine and Hindu— whisper to each other “Saya Ali is coming,” and they rush to the side of the road and cross their hands across their chests in a show of respect and to convey their greetings. Their parents convey prayers and blessing to the great mentor. The fragrance of mercy, an atmosphere of kindness and the warmth of love and respect radiated behind him wherever he walked. Saya Ali was the remedy for broken souls and a guiding star for the lost ones. He was the messiah for poor students. At tuition class, he never asked for a penny from those students who couldn’t afford the fees. He never finished a lesson unless every single student understood.

“Not just as a teacher or mentor, Saya Ali is the best as a human being” said Ishrat Bibi who is currently studying Public Health in Asian University for Women. “He teaches us not only school lesson but also life lessons. I can never forget one of Saya’s advises that he often used to tell us at class, ‘what you do today will determine what you are going to be tomorrow’,” she bursts into tears.

Saya Ali is the perfect definition of a good school teacher. His name is synonymous with mentorship. He was the end of hopelessness for students, and every student in northern Maungdaw dreamed of attending his class. A great teacher who taught from the heart; his love was bigger than his classroom, and his heart as clean as his white school shirt. He remembered every single student by name and would check-in on students who were absent from class. He illuminated thousands of souls with the light of wisdom and righteousness. Today, there are likely thousands of his pupils radiating his knowledge in countries around the world, including high-ranking Rakhine and Burmese officers in the armed forces and other civil services in Myanmar.

“My father is my teacher, my mentor, and everything” said Mohammed Ediris, the second son of Saya Ali. “He had a dream to fulfil after his retirement. He wanted to be a Member of Parliament (MP) in Myanmar like Master Jahangir. He often used to tell me that” the son mourns.

Saya Ali Ahmed is no longer with us in body, but we will cherish his deeds forever. His teaching and spirit will live on in you, me and all of his other pupils in the Rohingya community. To those who were moulded and enlightened by the wisdom and mentorship of Saya Ali, a responsibility is given; to give and to share, selflessly.

About the Author;

Mayyu Ali is a trusted pupil of Saya Ali Ahmed. Writing this short biography is an attempt to pay tribute to his greatest mentor.